1.1. Introduction – India and China, as two developing countries, are largely dependent on coal mining and thermal power for their economic growth. Coal, as a resource-driver of economy, gained momentum since 1800 onward and led industrial revolution till 1970s, when environmental concerns began to emerge. India and China, both fall among top 2 coal producing and utilizing countries. China is world’s largest coal producer contributing 47% to the global coal production in 2018, comparatively, Indian contrition was about 7%[efn_note]Global Energy Statistical Yearbook 2019 is Enerdata’s free online interactive data tool. Available at https://yearbook.enerdata.net[/efn_note]. It will not be wrong to infer that much of China’s economic might rests on the foundation of coal since 1960s onward, just like Germany’ economic power during 1900-1950 emanated completely from Ruhr coal mines (numbering 300) which sustained its vast network of military-industrial complexes. In Europe of that era, common saying was – ‘whoever rules the Ruhr, rules the Europe.’ Incidentally, in Ruhr after 150 years of mining, last coal mine was closed in 2018.

1.2. Indian Policy on Coal and Electricity –

| Table 1 – Top 12 Coal Producing Nations | ||

| S N | Country | Production (MT) |

| 1 | China | 3,874 |

| 2 | India | 764 |

| 3 | USA | 684 |

| 4 | Australia | 502 |

| 5 | Indonesia | 474 |

| 6 | Russia | 412 |

| 7 | South Africa | 257 |

| 8 | Germany | 169 |

| 9 | Poland | 123 |

| 10 | Kazakhstan | 118 |

| 11 | Turkey | 85 |

| 12 | Colombia | 84 |

| Total | 7,546 | |

| Source: Global Energy Statistical Yearbook 2019 | ||

Coal mining in India accelerated with the nationalization of coal mines in 1973, a period coinciding with the beginning of growing environmental concerns at global level. Subsequently, two government companies – Coal India Limited and National Thermal Power Corporation – were formed aimed at increasing coal production and thermal power generation, respectively. In sync with emerging global environmental legislation, India also put in place enactments on water, air, and forest which demanded compliance of stipulated conditions on industries, mining and developmental activities, most important being EIA notification 1994 by MOEFCC. Nevertheless, coal mining continued in a ‘business as usual’ manner, with scant regards to environment and compliance conditions, by both government and private companies. It is corroborated by the slapping of Rs 53,331 Crore penalties on Coal India subsidiaries in last two years, for over-production, implying gross violations of compliance conditions and collateral environmental damage.[efn_note] Debjoy Sengupta (2019). Coal India subsidiaries face Rs 53,331 crore penalties for over producing. Economic Times. 26 July 2019[/efn_note] If Coal India needs to pay these penalties, its finances will be critically hit. Its reserves, which stood at Rs 38,000 crore as on 1 April 2019, will fall short by Rs 15,000 Crore!

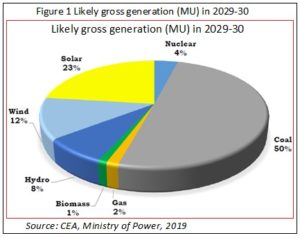

India, world’s number 2 coal buyer, plans to cut imports by a third. Coal imports are seen falling to below 150 million tons by the year ending March 2024, down from 235.2 million tons in the last fiscal[efn_note]Rajesh Kumar Singh (2019). India, world’s no. 2 coal buyer, plans to cut imports by a third. Live Mint. 1 August 2019[/efn_note]. To meet the import reduction goal, Coal India will aim to raise its annual output to 880 million tons by fiscal year 2024. A recent government report[efn_note] Central Electricity Authority (2019). Draft Report on Optimal Generation Capacity Mix for 2029-30. Ministry of Power, Government of India. February 2019[/efn_note] mentions that non-fossil fuel power sources, led by solar and wind, are seen generating 48% of gross generation, more than double what it was at the end of last year, while accounting for 65% of installed capacity. India had 80 GW of renewable capacity at the end of May 2019 and has set a goal to install 175 GW by 2022 [efn_note] Ibid. [/efn_note]. However, when juxtaposed with actual power generation by solar till 2018-19, the target of achieving 175 GW through RES is neither matched with the budgetary allocations nor any major incentives provided to solar investments and appears nothing more than hallucination. The report candidly admits that despite a boom in solar and wind energy projects, coal will continue to account for half of India’s power generation in 2030, as shown in figure 1.

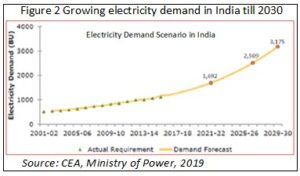

The electricity demand is likely to increase from 1115 BU in 2015–16 to 1692 BU in 2022, 2509 BU in 2027, and 3175 BU in 2030, as shown in figure 1, whereas likely gross electricity generation in 2029-30, as shown in figure 2.

The electricity demand is likely to increase from 1115 BU in 2015–16 to 1692 BU in 2022, 2509 BU in 2027, and 3175 BU in 2030, as shown in figure 1, whereas likely gross electricity generation in 2029-30, as shown in figure 2.

The draft National Electricity Plan (2016) [efn_note] Central Electricity Authority (2016). The Draft National Electricity Plan (2016) in India. Ministry of Power, Government of India[/efn_note] in India explains that “50 GW of coal power capacity is being built will cover for the increased demand without having to install new capacity for coal”, implying that no new capacity will be installed. This in reality is a false statement, for instance, Talabira-2 and Talabira-3 power plants are awaiting MOEFCC clearance, to generate 23 MTPA. Furthermore, newer coal lease are being granted on a regular basis, almost all of which are thermal coal.

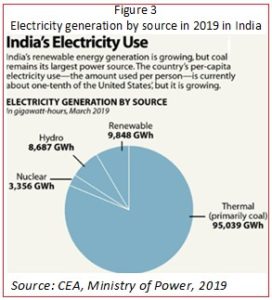

If we look at the source-wise energy production in India in 2019, share of actual generation by renewables (solar, wind and biomass) is 8.27% in total power generation. It is seen that by the end of year 2029-30, installed capacity by renewable energy sources (solar + wind) will skyrocket to 50% – 440 GW out of total installed capacity of 831 GW. Obviously it is a Herculean task, almost impossible to achieve, when viewed in the light of installing RES in the past. For instance, close to 33 years after India set up its first wind energy demonstration project of 1.15 MW in 1986 at Tuticorin, it emerges that a big source of clean energy has not been given the policy focus it deserves. The latest wind energy potential study carried out by Chennai-based National Institute of Wind Energy (NIWE) estimates 302 giga-watt (GW) at 100 metre above ground level (AGL). With only 35 GW installed so far, the country has a sizable untapped potential. It’s not just the low potential exploitation, but also its pan-India spread that is worrying—almost 90 per cent of this potential is concentrated in just five states[efn_note] Anon (2019). Renewable energy in India: In 33 years, India struggled to exploit just 12% of its wind energy potential. Down to Earth. 20 January 2019 [/efn_note].

If we look at the source-wise energy production in India in 2019, share of actual generation by renewables (solar, wind and biomass) is 8.27% in total power generation. It is seen that by the end of year 2029-30, installed capacity by renewable energy sources (solar + wind) will skyrocket to 50% – 440 GW out of total installed capacity of 831 GW. Obviously it is a Herculean task, almost impossible to achieve, when viewed in the light of installing RES in the past. For instance, close to 33 years after India set up its first wind energy demonstration project of 1.15 MW in 1986 at Tuticorin, it emerges that a big source of clean energy has not been given the policy focus it deserves. The latest wind energy potential study carried out by Chennai-based National Institute of Wind Energy (NIWE) estimates 302 giga-watt (GW) at 100 metre above ground level (AGL). With only 35 GW installed so far, the country has a sizable untapped potential. It’s not just the low potential exploitation, but also its pan-India spread that is worrying—almost 90 per cent of this potential is concentrated in just five states[efn_note] Anon (2019). Renewable energy in India: In 33 years, India struggled to exploit just 12% of its wind energy potential. Down to Earth. 20 January 2019 [/efn_note].

But all is not well with the renewable energy development in the country. In the past two years, renewable energy development has taken a backseat. Installation of renewable energy has gone down significantly in 2012-13 and 2013-14, compared to 2011-12. In 2011-12, about 3,200 MW of wind power was installed. But installation came down to 1,700 MW in 2012-13 and less than 1,246 MW in 2013-14 (till January, 2014). Solar power installation too has suffered. In 2011-12, 906 MW of solar power was installed. In 2013-14 (till January 2014) only 523 MW have been installed. By 2015, renewable energy accounted for about 12 per cent of the total electricity generation capacity and contributed about 6 per cent of the electricity produced in the country.[efn_note] Chandra Bhushan (2015). Growth of renewable energy in India. Down to Earth. 8 July [/efn_note] It will be relevant to mention here that states like Delhi, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu have policies to promote solar energy generation from rooftops of residential, commercial and industrial buildings.

But all is not well with the renewable energy development in the country. In the past two years, renewable energy development has taken a backseat. Installation of renewable energy has gone down significantly in 2012-13 and 2013-14, compared to 2011-12. In 2011-12, about 3,200 MW of wind power was installed. But installation came down to 1,700 MW in 2012-13 and less than 1,246 MW in 2013-14 (till January, 2014). Solar power installation too has suffered. In 2011-12, 906 MW of solar power was installed. In 2013-14 (till January 2014) only 523 MW have been installed. By 2015, renewable energy accounted for about 12 per cent of the total electricity generation capacity and contributed about 6 per cent of the electricity produced in the country.[efn_note] Chandra Bhushan (2015). Growth of renewable energy in India. Down to Earth. 8 July [/efn_note] It will be relevant to mention here that states like Delhi, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu have policies to promote solar energy generation from rooftops of residential, commercial and industrial buildings.

Lastly, the CEA’s analysis shows that India may be able to exceed one of its 2015 Paris Agreement’ commitments – reaching 40% of installed capacity from non-fossil fuel sources. But the report also sees annual carbon emissions from the power sector rising about 12% from levels expected in 2022 to 1.154 billion tons. The report didn’t include an assessment of what that means for another key India goal – cutting emissions intensity of gross domestic product by as much as 35% from 2005 levels.

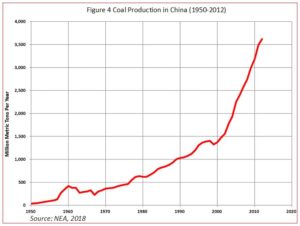

1.3. Chinese Policy on Coal and Electricity – Coal has been the dominant energy source in China and accounted for more than 70% of the total energy consumption for the past 20 years. The coal consumption in China achieved 4 billion tons in 2015, which is about half of global coal consumption. In 2015, China produced 3.7 billion tons of coal (including both steam coal and coking coal) and consumed 3.97 billion tons of coal, accounting for 47% of global production and around 50% of global consumption. Coal production in China has been on the rise and rise alone (figure 4).

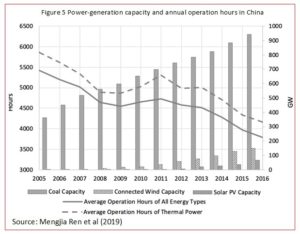

1.4. Has China Overinvested in Coal? – Year 2014 was watershed in the saga of thermal power in China. China continues to engage in massive expansion of coal power, thanks to policies that effectively subsidise and (over)incentivise coal power investment. It is the effect of the 2014 devolution of authority from the central government to local governments on approvals for coal power projects. The approval rate for coal power projects is about three times higher when the approval authority is decentralised, and provinces with larger coal industries tend to approve more coal power. In 2015 alone, China was building two coal plants per week. [efn_note] Mengjia Ren, Lee Branstetter, Brian Kovak, Daniel Armanios, and Jiahai Yuan (2019). China overinvested in coal power: Here’s why. VOX CEPR Policy Portal. 19 March 2019. At – https://voxeu.org/article/china-overinvested-coal-power-here-s-why [/efn_note] China approved nearly 200 gigawatts of new coal power capacity in 2015, even though the total capacity of the existing coal plants was 884 gigawatts.[efn_note] Ren, M, L G Branstetter, B K Kovak, D E Armanios and J Yuan (2019). Why has China over invested in coal power? NBER Working Paper 25437 [/efn_note]

From a political economy point of view, this devolution of authority exacerbated the risks of overinvestment. Local officials have been historically evaluated on the basis of the economic growth that took place in the region under their administration. By approving coal projects—even those that threatened to create an oversupply of coal-fired electricity—local officials could realise short-term political benefits from increased economic activity. By the time actual oversupply became apparent, the approving official might have been promoted to a higher position or to another province. This created a bias in favour of approval, even when there was a strong probability that the approved plants would crowd out green energy and reduce utilisation within the fleet of coal plants.

Despite all this, in the past five years, utilisation levels of all energy types fell sharply as growth in energy supply shot past energy demand (figure 5). Nearly 50% of China’s coal power plants faced net financial loss in 2018.[efn_note] Ji, X (2018). Half of thermal power companies in China face loss, need to increase subsidies imperatively. China (Hainan) Reform and Development Research Institute. Original paper in Chinese (Mandarian), translated in English by author, with the help of google translator [/efn_note] The presence of local coal production explains an additional 54 gigawatts of approved coal power in 2015 (other things equal), which is about a quarter of total approved capacity in that year.

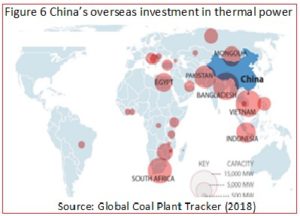

1.5. Chinese Policy on Coal and Thermal for Foreign Nations – As per a recent study[efn_note] Christine Shearer, Melissa Brown, and Tim Buckley (2019). China at a Crossroads: Continued Support for Coal Power Erodes Country’s Clean Energy Leadership. Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. January 2019 [/efn_note], China has committed US $ 21.3 billion for over 30 GW of coal-fired capacity across twelve countries, and proposed an additional US $ 14.6 billion in funding over 71 GW across 24 countries, in total, adding up to US $ 35.9 billion in funding for 102 GW of coal plant projects over 27 countries. The countries supported by Chinese finance with the most coal-fired capacity are Bangladesh, followed by Vietnam, South Africa, Pakistan, and Indonesia (figure 4). About 76 GW of the 102 GW of capacity is in pre-construction status. Incidentally, the 102 GW of coal proposals account for over one-quarter (26%) of global coal-fired capacity under development outside China, and over one-third (35%) of coal development outside China and India. In brief, 399 gigawatts (GW) of coal plants are currently under development outside China and Chinese financial institutions and corporations have committed or offered funding for over one-quarter of them (102GW).

The study further comments that China’s role as coal financier and developer primarily involves state-owned enterprises, with little involvement from private entities. The biggest lenders are Chinese policy banks: China Development Bank and the China Export-Import Bank, followed by Chinese state-owned commercials banks such as the Bank of China (BOC) and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC). The corporations most involved are large state-owned entities, including utility monopoly State Grid Corporation of China, infrastructure group China Energy Engineering Corporation, and power-giants State Power Investment Corporation and China Huadian Corporation.

The study further comments that China’s role as coal financier and developer primarily involves state-owned enterprises, with little involvement from private entities. The biggest lenders are Chinese policy banks: China Development Bank and the China Export-Import Bank, followed by Chinese state-owned commercials banks such as the Bank of China (BOC) and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC). The corporations most involved are large state-owned entities, including utility monopoly State Grid Corporation of China, infrastructure group China Energy Engineering Corporation, and power-giants State Power Investment Corporation and China Huadian Corporation.

Funding of these projects leaves China increasingly isolated as other nations move away from supporting coal. While Japanese and South Korean finance are the second and third highest supporters of coal plants globally, Japan’s prime minister and national power giant Marubeni have stated publicly their intention to transition away from thermal coal, along with Japanese insurers Dai-ichi Life and Nippon Life, while South Korea is no longer permitting new coal plants and is increasing coal taxes in a deliberate turn toward renewables. In terms of international financing for future coal plants by state-owned policy banks, China is by far the leader with 44 GW of capacity, followed by South Korea with 14 GW and Japan with 10 GW. Deeply concerned with the trend of heavy investment in coal, two renowned Chinese energy analysts with Global Energy Monitor concluded [efn_note] Aiqun Yu and Christine Shearer (2019). Time for China to Stop Bankrolling Coal. The Diplomat. 29 April 2019 [/efn_note] – “China is out of step with the world on coal, at home and abroad.”

An international news report infers [efn_note] Emily Feng (2019). China spends $36 bn on coal-fired power despite emissions goals. Financial Times. 22 January 2019 [/efn_note] that Beijing’s clean energy credentials have imperilled after funding projects in emerging markets. Chinese bankers and project planners like coal-backed projects because they are cheap. While they are restricted by Chinese pollution and emissions targets at home, they are free to fund coal-backed projects abroad. According to this news report – “They see the long-term financial, environmental and health consequences of these projects as the responsibility of the other side.”

1.6. China and India – The Road Ahead in Energy – The energy scenario envisaged by International Energy Agency in 2017[efn_note] IEA (2017). World Energy Outlook 2017. International Energy Agency. 2017 [/efn_note] is unique in the sense that for the first time it takes into account energy requirements of China and India into consideration, vis-à-vis population increase and mushrooming urbanization. In the New Policies Scenario, global energy needs rise more slowly than in the past but still expand by 30% between today and 2040, the equivalent of adding another China and India to today’s global demand.[efn_note] Ibid. [/efn_note] To meet rising demand, China needs to add the equivalent of today’s United States power system to its electricity infrastructure by 2040, and India needs to add a power system the size of today’s European Union.

China is entering a new phase in its development, with the emphasis in energy policy now firmly on electricity, natural gas and cleaner, high-efficiency and digital technologies, in domestic sector. The previous orientation towards heavy industry, infrastructure development and the export of manufactured goods lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty – including energy poverty – but left the country with an energy system dominated by coal and a legacy of serious environmental problems, giving rise to almost 2 million premature deaths each year from poor air quality.

However, it is not only coal, but China is investing in renewable energy too, but investment in coal continue to soar. According to a recent news report [efn_note] Reuters (2019). Chinese renewable energy investment abroad soars – but coal still dominant. South China Morning Post. 30 July 2019 [/efn_note], Chinese equity investment in solar, wind and coal power projects in Belt and Road Initiative countries surged from 2014 to 2019, with planned capacity up more than tenfold compared with the previous five-year period. The environmental group Greenpeace International too in its recent report[efn_note] Greenpeace (2019). China’s Equity Investments in Overseas Coal, Wind, and Solar Energy Projects. GREENPEACE International. 29 July 2019 [/efn_note] has inferred that – “China’s wind and solar power investments in belt and road countries amounted to 12.6 gigawatts since the initiative was launched in 2014. It had invested in just 0.45GW of solar before 2014.” The ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ is a Beijing strategy to boost economic and trade ties in dozens of countries in Asia, Europe and beyond, mostly through investments in energy and infrastructure.

By 31 June 2019, China had total hydropower capacity of around 354 GW, total wind capacity of 193 GW and solar capacity of 186 GW, according to official data. The increasing capacity has pushed electricity generated from renewable sources to 887.9 billion kilowatt hours (kWh) in the first half of 2019.[efn_note] NEA (2019). Half Yearly Energy Report. National Energy Agency, China. July 2019 [/efn_note]

Water shortage also played its role, along with other factors, in China’s shift from coal to renewables. Water scarcity has already hindered China’s energy development, manifested by plans to build coal-to liquids plants being abandoned in 2008. From 2000 to 2015, water withdrawal and consumption in China’s electric power sector, excluding hydropower, have increased from 40.75 and 1.25 billion cubic metre, respectively, to 124.06 and 4.86 billion cubic metre.[efn_note] Xiawei Liao and Jim W Hall (2018). Drivers of water use in China’s electric power sector from 2000 to 2015. Environmental Research Letters 13. 3 September 2018 [/efn_note] As population growth in China has stabilized, population no longer provides an upward pressure on power production and the corresponding water use. On the contrary, power production per capita has played the most significant role contributing to 103.40 and 3.84 billion cubic metre of water withdrawal and consumption increases respectively. It has been demonstrated that with uncoordinated policies power production may violate industrial water policies in the future, on both national and regional levels.[efn_note] Qin Y, Curmi E, Kopec G M, Allwood J M and Richards K S (2015). China’s energy-water nexus assessment of the energy sector’s compliance with the ‘3 Red Lines’ industrial water policy. Energy Policy. 82. [/efn_note], [efn_note] Liao X, Hall JW and Eyre N (2016). Water use in China’s thermoelectric power sector. Global Environmental Change. 41. [/efn_note]

Now let us look at scenario in India. The month of July was filled with announcements on policy amendments and regulations. Some of the important policy announcements included the deviation settlement mechanism (DSM), solar park program, standardization issues, interstate transmission systems (ISTS), among others. There were more policy changes at the central level as compared to the state level. Most significant of these is notification on ‘roles and responsibilities of DISCOMs under the 12 GW Solar CPSU Program.’[efn_note] Ministry of New & Renewable Energy (2019). Roles and Responsibilities of DISCOMs Under the 12 GW Solar CPSU Program. Notification by MNRE. 3 July 2019 [/efn_note]

On the one hand government talks of promoting renewable energy on an unprecedented level while on the other hand, it has started the process of opening 27 new coal blocks for commercial coal mining.[efn_note] Debjoy Sengupta (2019). Center readies 27 coal blocks for commercial mining. Economic Times. 5 August 2019 [/efn_note] Centre has decided to auction 27 coal blocks to private companies who can sell 25 per cent of the produce in the open market at a premium of 15 per cent over their bid price for winning these blocks. Rest of the coal is meant for captive consumption intended for iron & steel, cement, and captive power plants.

Blocks would be auctioned in three tranches – 8th, 9th and 10th. Under the 8th tranche, 20 blocks are on offer and it is for iron & steel, cement and captive power plants, excluding steel makers using coking coal. These blocks include Maharashtra (10), Chhattisgarh (4), West Bengal (4), Jharkhand (1) and Madhya Pradesh (1). The 9th Tranche of blocks on offer includes 6 blocks for iron and steel producers only. Under this tranche the centre has offered 5 blocks from Jharkhand and from Madhya Pradesh. The 10th Tranche is for a single block meant for iron & steel, cement and captive power plants, excluding steel makers using coking coal. The centre has offered only one block from Odisha under this tranche. According to the timeline prepared by the centre, financial bidding are to be held between 10th October and 8th November 2019 while final allotments are likely to happen by 11th November 2019.

However, in harnessing solar power, there is one bone of contention which has the potential to become a conflict, in future not so distant. China is spearheading a movement to build a globally interconnected smart grid that can connect solar channels across borders. India has stayed out as it is clubbed with the BRI[efn_note] Prashant Mukherjee (2019). Hostility to China’s Belt and Road Initiative can thwart India’s solar-energy ambitions. Economic Times. 31 July 2019 [/efn_note] even though it dovetails with Narendra Modi’s goal of ‘One World, One Sun, One Grid’ – putting a grave question-mark on the future of India-led International Solar Alliance.

1.7. Climate Change – Contemporary and Past – Many people have a clear picture of the “Little Ice Age” (from approx. 1300 to 1850). That it was extraordinarily cool in Europe for several centuries is proven by a large number of temperature reconstructions using tree rings, for example. There are also similar reconstructions for North America. It was assumed that the “Little Ice Age” and the similarly famous “Medieval Warm Period” (approx. 700-1400) were global phenomena.

Now an international group of scientists at the Center for Climate Change Research, University of Bern, Switzerland is painting a very different picture of these alleged past global climate fluctuations. They have inferred – “that there is no evidence that there were uniform warm and cold periods across the globe over the last 2,000 years.” [efn_note] Raphael Neukom, Nathan Steiger, Juan José Gómez-Navarro, Jianghao Wang and Johannes P. Werner (2019). No evidence for globally coherent warm and cold periods over the preindustrial Common Era. Nature, 571, July 24, 2019 [/efn_note], [efn_note] Raphael Neukom, Nathan Steiger, Juan José Gómez-Navarro, Jianghao Wang and Johannes P. Werner (2019). Consistent multidecadal variability in global temperature reconstructions and simulations over the Common Era. Nature Geoscience, 12, July 24, 2019 [/efn_note]

In contrast to pre-industrial climate fluctuations, current, anthropogenic climate change is occurring across the whole world at the same time, finds new studies. Moreover, the speed of global warming is higher than it has been in at least 2,000 years.[efn_note] Ibid. [/efn_note] Two major inferences of this study are – Climate fluctuations in the past varied from region to region and consistent multi-decadal variability prevailed over the Common Era. The largest warming trends at timescales of 20 years and longer occur during the second half of the twentieth century, highlighting the unusual character of the warming in recent decades.

Lead scientist of this study Prof Raphael Neukom explains – “It’s true that during the Little Ice Age it was generally colder across the whole world, but not everywhere at the same time. The peak periods of pre-industrial warm and cold periods occurred at different times in different places.”[efn_note] Ibid. [/efn_note] In a nutshell, the real global climate change is happening for the first time in the history of humanity, sensu stricto, and bears grave implications for the life on Earth.

Coming towards the end, it can be safely surmised that the mode of energy production in two most populous countries of world – China and India – will substantially influence the course of climate change and consequently both bear grave responsibility on their shoulders towards future generations of the globe. Whether the wise leaders of these two countries will succeed or fail in dealing with this challenge, is embedded in the womb of future.

Author – Arun Kumar Singh

References

Recent Comments