The monarchy of King Coal[i] is being slowly surrendered. Sun is economically overpowering him; climate change calls for his immediate dismissal and communities are fed up with the land and accompanying resources he has been devouring in the name of providing “cheap” power. In India, love with this monarch and his dirty and undemocratic ways seems to be more for the need of the rent-seekers and status quoists. Economics, environment, and equity concerns would call for different alternatives. The most recent means of sustaining him is the “self-dependence” (Atmanirbhar) plank, ironically with Foreign Direct Investments and total privatization and all possible props. Yet his days are numbered.

The monarchy of King Coal[i] is being slowly surrendered. Sun is economically overpowering him; climate change calls for his immediate dismissal and communities are fed up with the land and accompanying resources he has been devouring in the name of providing “cheap” power. In India, love with this monarch and his dirty and undemocratic ways seems to be more for the need of the rent-seekers and status quoists. Economics, environment, and equity concerns would call for different alternatives. The most recent means of sustaining him is the “self-dependence” (Atmanirbhar) plank, ironically with Foreign Direct Investments and total privatization and all possible props. Yet his days are numbered.

Energy – Coal and Fiscal Losses

|

Coal Consumption in MT by Sector (2018-19) |

|

| Power | 637.949 |

| Steel | 17.662 |

| Cement | 8.817 |

| Sponge Iron | 12.231 |

| Others | 56.135 |

Power Sector is the major user of coal, consuming over 87 percent of the coal produced. Government of India, for the first time, sought to have an integrated energy policy[i] with the goal of providing energy security for all in 2006.

The vision was to reliably meet the demand for energy services of all sectors. This particularly included the lifeline energy needs of vulnerable households in all parts of the country with safe, clean, and convenient energy at the least-cost. The policy aimed to achieve this in a technically efficient, economically viable and environmentally sustainable manner using different fuels and forms of energy, both conventional and non-conventional, as well as new and emerging energy sources to ensure supply at all times with a prescribed confidence level considering that shocks and disruption can be reasonably expected. The policy aimed at a minimum life-line requirement of 1 KwH/Household/day by 2012 and 100 percent access by 2010. Unfortunately, both these targets were missed.

| Installed Capacity as of 30.09.2020

https://cea.nic.in/monthlygeneration.html) |

||

| Fuel | MW | % of Total |

| Total Thermal | 2,31,321 | 62.0% |

| Coal | 1,99,595 | 53.6% |

| Lignite | 6,260 | 1.7% |

| Gas | 24,957 | 6.7% |

| Diesel | 510 | 0.1% |

| Hydro (Renewable) | 45,699 | 12.3% |

| Nuclear | 6,780 | 1.8% |

| RES* (MNRE) | 89,229 | 23.9% |

| Total | 373,029 | |

The Government brought out a draft energy policy in 2017, with the following key objectives: Access at affordable prices, Improved security and Independence, Greater Sustainability and Economic Growth. The policy aims to ensure that electricity reaches every household by 2022 as promised in the Budget 2015-16 and proposes to provide clean cooking fuel to all within a reasonable time. Thus, it has shifted the goal post from 2012 to 2022 and on clean fuels it remains open ended. The concern with providing energy access to all though reiterated by the government it is clearly a case of lack of political will and intent as well as affordability, as the capacity needed to reach the last household exists. Between the period of the two policies, the total installed capacity for electricity generation more than doubled from 168 GW to 3773 GW, whereas to provide the life-line requirement to all households a mere 20 GW would be sufficient. The need for providing cheap and reliable energy to a population which is likely to be stable at around 1.7 Billion is daunting. The policy and regulatory processes and the subsequent direction of investments in the energy sector is going to be crucial to all aspects of human life in this pandemic and post-pandemic era. The reality is that the demand for power did not match the anticipated growth rate and the production of coal has been even less with the pandemic.

The entire impetus for liberalised economic growth and privatisation of energy production, supply and distribution was based on the premise of financial stability and competitiveness leading to the efficiency. This very objective has been belied in the growth of energy production systems and particularly the coal-based power plants. The thermal power sector accounts for $40-60 billion of potentially stranded assets that are continuing to trouble the Indian banking sector. Fifteen GW out of the stressed 40 GW has not yet been commissioned, as identified in the report of the Standing Parliamentary Committee on Energy. The committee found the ‘stressed’ value of the 34 stranded assets to be Rs236,619 crore ($33.5b) in total, with stranded loans of Rs176,130 crore ($25b) and an equity value of Rs60,489 crore ($8.5b), as of March 2018. In their final report, the Parliamentary Committee identified key reasons for stress in India’s thermal power sector, including: • Lack of fuel due to cancellations in assigned coal linkages or projects set up without any coal linkages; • Lack of PPAs with state discoms; • Inability of promoters to infuse equity and working capital; • Contractual and tariff-related disputes;

100 out of 110 GW of generation capacity has been added recently is from coal-based plants while the demand has not kept pace. Available capacity is now more than the demand and peak power shortage has reduced from 8.7% in 2012-13 to 0.2% in 2018-19, which is due to mismatch in the production and distribution and other factors.

100 out of 110 GW of generation capacity has been added recently is from coal-based plants while the demand has not kept pace. Available capacity is now more than the demand and peak power shortage has reduced from 8.7% in 2012-13 to 0.2% in 2018-19, which is due to mismatch in the production and distribution and other factors.

Banks are currently saddled with loans worth Rs 4 trillion pertaining to the power sector, most of which are likely to turn sour. The National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) through the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) is ultimately forcing banks to have 50 per cent provisioning euphemistically known as “haircuts”. That’s Rs 2 trillion loss of public money[i].

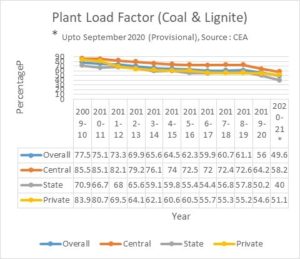

Even existing coal-based power projects are operating at low Plant Load Factors (PLFs), imposing heavy costs on state power utilities. One reason for this is that the off-peak demand for electricity is not sufficient to allow the excess coal-based generation to operate at full capacity.”[ii]

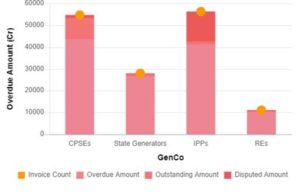

‘Report on Performance of State Power Utilities’ published by Power Finance Corporation Limited (PFC), the accumulated losses and outstanding debt of DISCOMs have increased from Rs.2, 53,700 Crore and Rs.3, 04,228 Crore respectively from the year 2012-13 to Rs.3, 60,736 crore and Rs.4, 06,825 crore respectively in the year 2014-15. The total outstanding loans for all utilities increased from Rs 6,70,708 crore as on March 31, 2015 to Rs 7,26,721 crore as on March 31, 2016. The Government in its recent trend of having a contrived indigenised acronym has set up a portal – Payment Ratification And Analysis in Power procurement for bringing Transparency in Invoicing of generators – “Praapti”, which after all these kinds of restructuring of the debts show a whopping Rs 1.33 lakh crore at the end of August, 2020.

‘Report on Performance of State Power Utilities’ published by Power Finance Corporation Limited (PFC), the accumulated losses and outstanding debt of DISCOMs have increased from Rs.2, 53,700 Crore and Rs.3, 04,228 Crore respectively from the year 2012-13 to Rs.3, 60,736 crore and Rs.4, 06,825 crore respectively in the year 2014-15. The total outstanding loans for all utilities increased from Rs 6,70,708 crore as on March 31, 2015 to Rs 7,26,721 crore as on March 31, 2016. The Government in its recent trend of having a contrived indigenised acronym has set up a portal – Payment Ratification And Analysis in Power procurement for bringing Transparency in Invoicing of generators – “Praapti”, which after all these kinds of restructuring of the debts show a whopping Rs 1.33 lakh crore at the end of August, 2020.

| Penalty for Illegal Mining (in Rs Cr) | |

| Subsidiary | Penalty |

| CCL | 13,568.50 |

| ECL | 2,178.14 |

| MCL | 11,212.81 |

| SECL | 10,182.62 |

| BCCL | 17,344.46 |

| Total | 54,486.53 |

Coal in India, in recent times, has been in debate for several wrong reasons, including corruption and stranded investments, climate impacts and pollution, environmental and human rights violations. The allocation of coal mining leases has been controversial. Despite the claims of transparent auctions, the 11 tranches of auction and progressive sweetening of the auction, the process is clearly coloured. The compliance of mining and other regulations has been lackadaisical. The amount due from the state owned CIL itself is over fifty thousand crores (` 8 Billion USD)

The Integrated Energy Policy 2006 warned, “Large estimates of total coal resources give a false sense of security because current and foreseeable technologies convert only a small fraction of the total resource into the mineable category. The capacity of PSUs engaged in exploration has restricted the pace of proving indicated and inferred resources. This limited capacity, coupled with the economics of opencast mines versus underground mines, gives only limited incentive to explore for coal beyond 300m depth.” Even if we assume that coal will last until 2060 at the slightly enhanced levels of 1 Billion Tonnes per annum, it is merely 40 Billion tonnes. It is estimated that nearly 220 Billion Tonnes of Coal will remain unused as the future unfolds. Therefore, all the exploration and opening up of new mines are going to increase the loss to the exchequer of the accompanying resources of land, forests, and very precious water resources. The costs associated with these actions are also going to be a loss for the country and future generations.

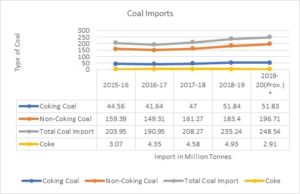

Coal consumers are free to import coal based on their requirement. Superior quality non-coking coal is imported mainly by coast-based power plants and other industrial users viz., paper, sponge iron, cements, and captive power plants, on consideration of transport logistics, commercial prudence, export entitlements and inadequate availability of such superior coal from indigenous sources.

Coal consumers are free to import coal based on their requirement. Superior quality non-coking coal is imported mainly by coast-based power plants and other industrial users viz., paper, sponge iron, cements, and captive power plants, on consideration of transport logistics, commercial prudence, export entitlements and inadequate availability of such superior coal from indigenous sources.

The import of coal is also embroiled in typical trade-based money laundering. The Department of Revenue Intelligence has been investigating on over 40 coal importers for malpractices estimated to be of the order of Rs 49,000 Cr (`7 Billion USD). The concessions granted for private players on the basis of the argument that it will reduce imports seems ineffective.

| Coal Cess and National Clean Energy and Environment Fund | |||

| Year | Coal Cess Collected | Amount transferred

|

Amounts financed from

NCEEF |

| 2010-2011 | 1,066.46 | 0 | 0 |

| 2011-2012 | 2,579.55 | 1,066.46 | 220.75 |

| 2012-2013 | 3,053.19 | 1,500.00 | 246.43 |

| 2013-2014 | 3,471.98 | 1,650.00 | 1,218.78 |

| 2014-2015 | 5,393.46 | 4,700.00 | 2,087.99 |

| 2015-2016 | 12,675.60 | 5,123.09 | 5,234.80 |

| 2016-2017 (RE) | 28,500.00 | 6,902.74 | 6,902.74 |

| 2017-2018 (BE) | 29,700.00 | 8,703.00 | 0 |

| Total | 86,440.24 | 29,645.29 | 15,911.49 |

Since 2011, India has been collecting a cess on coal[iii]. Initially it was called the National Clean Energy Fund and later it was renamed the National Clean Energy and Environment Fund. It was imposed under section 83 of Finance Act, 2010 on row coal, lignite and peat produced in India. The cess has come into force from 01.07.2010 and it is collected as duty of excise.

The cess has been subsumed under GST from 1st July, 2017[iv]. Arrear Collection: The actual collection of arrears of Central Excise duties in 2017-18 was Rs 1866 Crore. R.E. 2018-19 and B.E. 2019-20 for collection of arrears of Central Excise duties are Rs 2338 Crore and Rs 3000 Crore respectively. If we look at the total fund collection and the unconstitutional way the cess collected for a purpose has been subsumed, it shows nearly 14 Billion Dollars opportunity to transform our energy systems has been frittered away.

Climate and Human Impacts and Implications

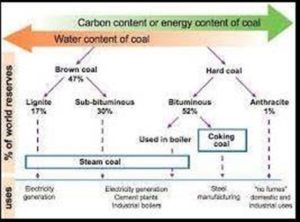

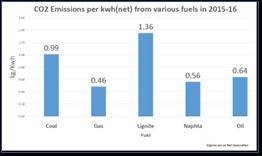

Coal is characterised by the energy content and the water content from Lignite to Anthracite coals. Indian coal and lignite deposits are of poor quality mostly sub-bituminous with high ash, heavy metal and trace radioactive elements. The poor quality of coal leads to almost a Kg/KwH of CO2 emissions from coal based thermal plants.

The IPCC special report released last year clearly warns of a runaway climate change leading to a global crisis. The efforts needed to stay within limits demand a very concerted efforts, even with which the task is humungous. Energy systems contribute to a large proportion and among these sources coal is undoubtedly the deadliest. It is therefore an urgent necessity to transition from coal. The climate footprint of coal mining and thermal power is large and significant.

The IPCC special report released last year clearly warns of a runaway climate change leading to a global crisis. The efforts needed to stay within limits demand a very concerted efforts, even with which the task is humungous. Energy systems contribute to a large proportion and among these sources coal is undoubtedly the deadliest. It is therefore an urgent necessity to transition from coal. The climate footprint of coal mining and thermal power is large and significant.

The generation of power and the corresponding emissions as estimated by the Central Electricity Authority[v] for its baseline reports indicates that in 2017-18, the Electricity Sector alone resulted in emissions of nearly a Billion Tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere.

There has been a steady raise in the emissions from the sector over the past few years. Despite the claims of reduction in intensity of the carbon emissions, there has been no variation over the past few years. Since a number of plants have been established in the past decade, this would portend long term emissions from these units.

There has been a steady raise in the emissions from the sector over the past few years. Despite the claims of reduction in intensity of the carbon emissions, there has been no variation over the past few years. Since a number of plants have been established in the past decade, this would portend long term emissions from these units.

The Central Electricity Authority estimates that the total coal requirement in 2027 would be around 900 Million Tonnes and would produce nearly 1250 Billion Units of Power.

Thus, unless reversed India’s coal-led power generation systems alone will contribute an annual emission load of over a Billion Tonnes of CO2 in the atmosphere. Long-term implications of these emissions may demand early retirement of many of these plants.

| EMISSION DATA | |||||

| 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | |

| Absolute Emissions Total (tCO2) | 72,73,64,166 | 80,53,84,471 | 84,62,61,119 | 88,83,41,294 | 92,21,82,366 |

| Absolute Emissions OM (tCO2) | 72,73,64,166 | 80,53,84,471 | 84,62,69,450 | 88,83,41,294 | 92,21,82,366 |

| Absolute Emissions BM (tCO2) | 17,12,18,145 | 18,08,08,003 | 18,68,63,159 | 18,84,56,479 | 19,43,01,045 |

| Net Imports (GWh) | 3,405 | 1,594 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Share of Net Imports (% of Net Generation) | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

Coal Based Thermal Power plants were to adhere to stricter pollution norms from December 2017. The Government did not  make any effort or push the industry to initiate action on this notification issued in 2015. However, it surreptitiously approached the Supreme Court, with a dubious report to seek its intervention in extending the period for compliance to 2022. Coal Based thermal power plants are the undoubtedly the biggest emitters of GHGs. Promotion of such a destructive energy source in a period when renewables have become even financially attractive and dilution of the norms for their emissions clearly indicates the utmost lack of concern of the government towards the environment and in this case the very health of the citizens. Now the Supreme Court is seized with it and has asked a time-table of installation of emission control equipment in each coal-based power plants.

make any effort or push the industry to initiate action on this notification issued in 2015. However, it surreptitiously approached the Supreme Court, with a dubious report to seek its intervention in extending the period for compliance to 2022. Coal Based thermal power plants are the undoubtedly the biggest emitters of GHGs. Promotion of such a destructive energy source in a period when renewables have become even financially attractive and dilution of the norms for their emissions clearly indicates the utmost lack of concern of the government towards the environment and in this case the very health of the citizens. Now the Supreme Court is seized with it and has asked a time-table of installation of emission control equipment in each coal-based power plants.

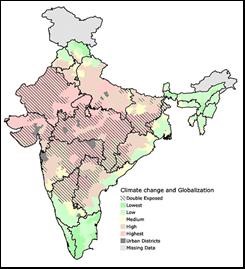

The implications of climate change are severe for those in the coal belt[vi]. Studies on the impacts of global warming and globalisation indicates a strong overlap of the areas in central India.

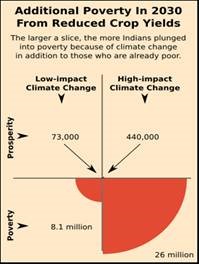

This portends the possibility of enhancing poverty and vulnerability of the communities living in this region. It seems so blatantly unjust that not only resources for the profit and growth of other regions are being provided by the communities in coal-bearing areas the revenues raised by government is not being utilised for the welfare of the people in the region to enable them to become more climate resilient. Instead their lives are being sacrificed in the name of development. An estimate of the potential number of people, who will be impoverished because of reduced crop yields, places it between 8 and 26 million between now and 2030. This calls for massive corrective actions and investments.

The performance audit by the Auditor General states “Mining operations damage the environment and ecology to an unacceptable degree, unless carefully planned and controlled. Therefore, there is a need for balance between mining and environmental requirements. Further, the problem of mining-induced displacement and resettlement poses major risks to social sustainability. Therefore, the coal mining companies have a special responsibility towards environment protection and social development.” However, in reality this seems to be completely overlooked.

The performance audit by the Auditor General states “Mining operations damage the environment and ecology to an unacceptable degree, unless carefully planned and controlled. Therefore, there is a need for balance between mining and environmental requirements. Further, the problem of mining-induced displacement and resettlement poses major risks to social sustainability. Therefore, the coal mining companies have a special responsibility towards environment protection and social development.” However, in reality this seems to be completely overlooked.

The environmental clearance conditions stipulate that a compliance report of all the conditions under which the clearance is granted is prepared and submitted after monitoring and assessment. These documents are also mandated to be on the website of promoter and on the Ministry’s website. Of the 700 mines granted clearances and listed in the website, 297 have not submitted even a single compliance report. The CAG[vii] in 2011 pointed out that all 239 mines in CIL, which existed prior to 1994, when the first notification was issued, 48 open cast mines, 170 underground mines and 21 combined mines were found to be working without environmental clearance. The situation has only worsened over the decade.

The Comptroller and Auditor General in its performance audit report of 2016[viii] pointed out that “In 25 per cent cases, the Environment Impact Assessment reports did not comply with Terms of Reference and in 23 per cent cases they did not comply with the generic structure of the report. Cumulative impact studies before preparing the Environment Impact Assessment reports was not made a mandatory requirement, thus the impact of a number of projects in a region on the ecosystem was not known. Ministry had not followed due process in issue of Office Memoranda and the Office Memoranda so issued had the effect of diluting the provisions of original notification.”

The report also noted that there was no provision for the Project Proponents to fulfil their commitments in a time bound manner and to ensure that the concerns of the local people were included in the final Environment Assessment and Environmental Clearance granted by the State. The public hearing process did not have quorum requirement to participate in the public hearing process. Commitments made by Project Proponents in Environment Impact Assessment report during public hearing was also not monitored. Besides, the reservations expressed during the public hearings were not included in the Environment Impact Assessment reports.

| Impacts of Mining on Water |

| Open cast mining/quarrying /excavation not intersecting ground water table |

| Affecting natural surface water regime

Affecting ground water recharge regime |

| Open cast mining/excavation intersecting ground water table |

| Pumping of ground water

Declining of water table Affecting natural surface water regime Affecting ground water recharge regime Affecting natural springs |

| Underground mining |

| Affecting ground water recharge regime

Shallow aquifers Deep aquifers Affecting ground water flow direction Affecting ground water recharge |

| CBM/ Underground Coal Gasification |

| Ground water resource/potentials-drying of upper aquifers and impact on deep and cognate aquifers |

The total area under mining and abandoned after mining is exactly not known. The total land under mining is estimated to be greater than 1.30 million hectares. Land under coal mining and abandoned coal mines alone is around 0.36 million hectares. Land required depends on the Geological occurrence and the surface environment however on an average 6-9 hectares per million tonnes is destroyed. This could be much higher areas of high slope. The problem becomes acute in densely settled lands. A large tract of land is continuously impacted by Coal Fires. This too happens to be in a densely populated region in the Asansol-Dhanbad region.

Wherever the mines have breached the ground water table the adjoining areas have had to suffer the consequences of lowering of the water table and directly resulting in drying up of wells and other near surface sources. The long-term effects on groundwater are even graver. In areas such as in the north-east, the high sulphur content leads to a large volume of Acid Mine Drainage.

It is clear that intersection of water table by the mining industries must be considered seriously as in several places the major resources lies beneath the water table. The breaching of the ground water table must be subject to stricter regulation as the very basis of survival of the local communities is sacrificed at this stage.

Merely to say that the mine water is put to “gainful” use can lead to unsustainable management of the aquifer. While this may include several uses such as water supply to adjacent area, utilization for dust suppression by the industry, utilization by the mining industry for its different purposes, supplying to local communities, to water supply agencies, utilization for artificial recharge etc., it will be tantamount to mining water.

The recent tragedy where the bodies of the miners trapped in Meghalaya’s Rat-hole mines were so decomposed as the mine waters would have be more acidic. Occupational hazards of mining are largely neglected, and we estimate per 5 Million Tonnes of coal input to plant there one person losing life and about 8 suffering disabling injuries. Besides there are also hazards associated with coal washing, transportation and disposal of wastes. Safety could also be correlated to environmental practices which decides how the operational design exists which is usually bad in context of mining. The assessment by CAG also revealed that Initial and periodical medical examinations were being done for the company employees while only 1.58 per cent to 7 per cent of contractors’ employees underwent medical examination, although mandatory.

Human Rights violation in coal mining begins with non-provision of adequate information to ensure Free Prior and Informed Consent. The land is acquired under the Coal Bearing Areas Act which provides no scope for the people affected to question the need for the project and the quantum of land. The principle of eminent domain is used by the state to deny the basic right to be informed, to participate and ensure their rights are not trampled with in the process of establishment.

The Universal Declaration of human rights and the fundamental rights are supposed to guarantee right to equality. However, the state policies and high-handedness of government, corruption and intimidation by the industry, more recently through the use of “goons” has forced many a community faced with displacement through mining. The right to life includes the right to live in a safe environment which is denied to not only to these people who are displace but also to those working in the mines and living in surrounding areas. Complaints of damage to houses due to blasting is out rightly denied and has become a common phenomenon in villages adjoining the mines. Since safety in the mines itself is largely compromised as most of the actual mining operations are outsourced to contractors, the concerns of the community are never recognised and even if recognised never addressed to the satisfaction of the affected.

[i] India’s Coal Conundrum:Dirty Past, Murky Future; Fair Finance India, 2019

[ii] https://www.moneylife.in/article/to-what-end-are-psbs-continuing-to-finance-coal-fired-power/54457.html

[iii] https://doe.gov.in/sites/default/files/NCEF%20Brief_post_BE_2017-18.pdf

[iv] https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/ub2019-20/rec/allrec.pdf

[v] http://www.cea.nic.in/tpeandce.html

[vi] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S095937800400010X

[vii] https://cag.gov.in/sites/default/files/audit_report_files/Union_Performance_Commerical_Coal_India_Limited_Corporate_Social_Responsibility_9_2011.pdf

[viii] https://cag.gov.in/sites/default/files/audit_report_files/Union_Government_Report_39_of_2016_PA.pdf

[i]https://niti.gov.in/planningcommission.gov.in/docs/reports/genrep/rep_intengy.pdf

[i]https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7522

Recent Comments